This is an old revision of the document!

Jadual Kandungan

Cebisan Sejarah Kuantan

Koleksi beberapa peristiwa di sekitar Kuantan, yang ada direkodkan dalam sumber-sumber setakat yang dapat diperolehi di Internet, dan disusun menurut kronologi peristiwa. Antara sumber utama ialah Arkib Negara Malaysia, keratan-keratan akhbar di NewspaperSG (arkib digital akhbar tempatan yang beribu pejabat di Singapura sejak tahun 1827, kelolaan National Library Board (NLB) of Singapore), serta MyRepositori (arkib digital akhbar tempatan, kelolaan Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia). Pada setiap peristiwa, selain ringkasan liputannya, ditambahkan juga beberapa catatan ringkas atau capaian mengenai perkara atau tempat yang berkaitan, berdasarkan makalah-makalah dan kertas kerja para ilmuwan dan pengkaji sejarah, setakat yang ada di Internet sahaja.

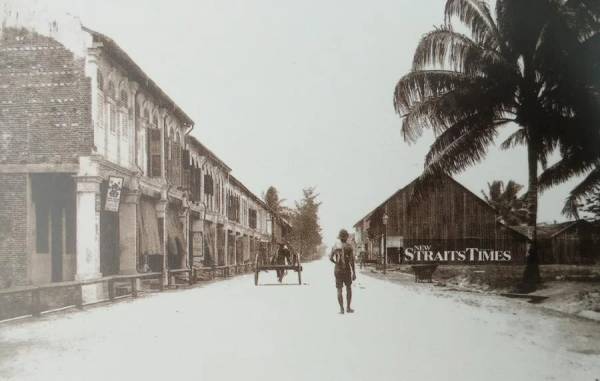

Kuantan, awal kurun ke-20: “A street in Kuantan during the first decade of the 20th century.” (Alan Teh Leam Seng @ New Straits Times, May 5, 2019: |"Tracing Pahang's three capitals").

Kronologi Sejarah Kuantan

Kronologi peristiwa, menurut beberapa sumber dan usaha pensejarahan lain di Internet yang memfokus (atau ada menyentuh) perihal Kuantan dan kawasan sekitarnya:-

8,000 - 2,000 SM: Sejarah Purbakala

“Sejak tahun 1977, beberapa orang ahli kajipurba telah menjalankan penyiasatan dengan membuat beberapa penggalian tanah secara ilmiah di beberapa buah tempat di Pahang (dan negeri lain juga), iaitu di gua batu di gunung-ganang, di tempat berhampiran dengan sungai, di tanah perlombongan lama dan juga di tempat lapang yang dipercayai di situ ada tertanam barang peninggalan zaman dahulu kala. … Dalam penyiasatan yang telah dibuat, mereka telah menjumpai banyak benda dan perkakas yang tertentu dan diperbuat daripada batu, tembikar, gangsa dan besi-kuno buatan orang zaman purbakala, dan di beberapa buah tempat di Pahang terutama di gua batu yang disebut Kota Tongkat, Kota Gelanggi dekat Pulau Tawar, di Gua Kecil dekat Raub, di Gunung Senyum, di Bukit Cintamanis dekat Karak, di Sungai Lembing, di Tersang di tepi Sungai Lipis, di Sungai Selinsing, di Sungai Tui, di tepi Sungai Tembeling di tempat yang bernama Nyong, Teluk Lubuk, Batu Pasir Garam, Bukit Jong dan di Kampung Pagi di persimpangan Sungai Tembeling dengan Sungai Pengau, di lombong emas Tui, di Hulu Tanum atau Hulu Jelai, di daerah Kuantan dan di beberapa buah tempat sepanjang Sungai Pahang. … Berdasarkan kepada benda dan perkakas serta kesan yang telah dijumpai itu, ahli kajipurba telah mengatakan: manusia Zaman Batu Pertengahan yang telah bermastautin di Pahang (dan juga negeri lain di Semenanjung Tanah Melayu) tinggal di gua batu dan di bawah guguk di kawasan pergunungan negeri itu. Ahli kajimanusia dan ahli sejarah pula berpendapat: mereka adalah kumpulan manusia yang pertama datang ke Semenanjung Tanah Melayu dari tanah besar benua Asia dalam lingkungan dari tahun 8,000 hingga tahun 2,000 sebelum tahun masihi. Tetapi manusia Zaman Batu Pertengahan itu telah meninggalkan Semenanjung Tanah Melayu dan berpindah ke timur iaitu di pulau-pulau Lautan Pasifik. Ahli kajimanusia mengagakkan mereka itulah nenek-moyang kepada rumpun bangsa Melanesia yang mendiami Pulau New Caledonia dan Pulau Papua (Irian Barat dan New Guinea).” (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 27).

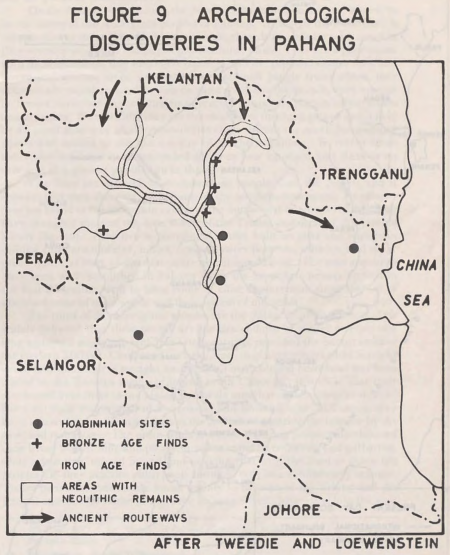

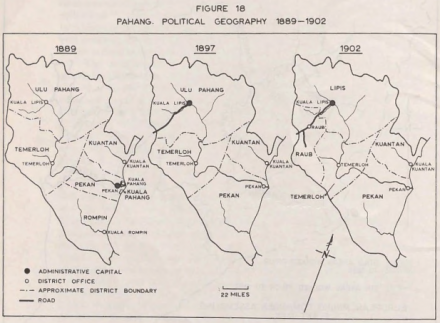

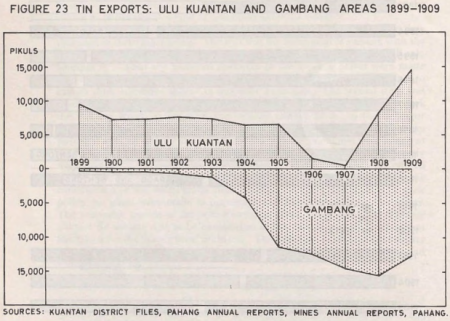

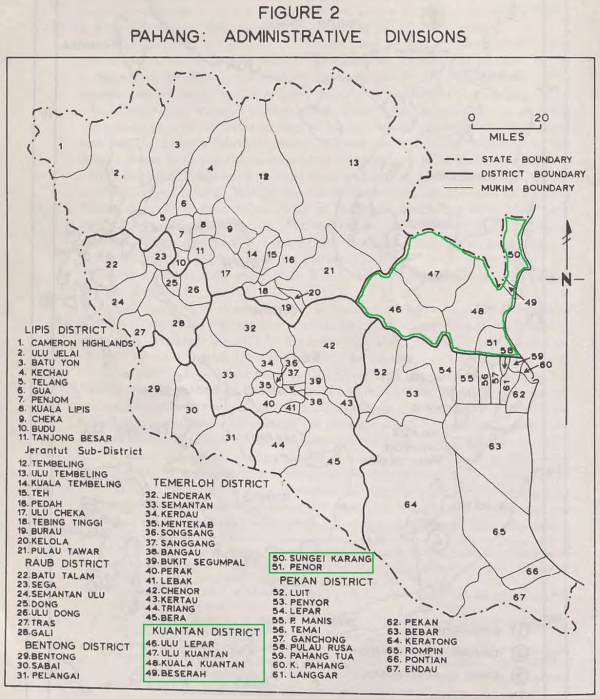

“FIGURE 9 ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES IN PAHANG”

“Many thousands of years have elapsed since man first entered Pahang, and many small groups may have passed through or perished without leaving any evidence, but the conviction which emerges from a study of the published evidence is that this was a sparsely settled land until very recent times. Archaeology provides evidence about four cultural groups which entered Pahang from the north prior to the present millenium. Two of these groups were stone-age settlers and two appear to have been expatriate miners who brought with them a metal culture from their more civilized homelands to the north of the Peninsula (fig. 1). The first to leave evidence of their existence were a people who were known as Hoabhinians after the locality in Tonkin where their artifacts were first identified. They arrived in Malaya some time between the fifth and second milleniums B.C. and entered Pahang via the interior routeways from Kelantan (fig. g). These settlers were essentially a hunting and gathering people who used flaked stone implements and lived in limestone caves and rock shelters. It seems that they were unfamiliar with any form of agriculture and lacked both the inclination and the equipment to clear the forest. At any given time their numbers might be reckoned in tens rather than hundreds and there is no evidence that they moved further into Pahang than the limestone areas in the vicinity of Bentong, near the middle Pahang River, and inland from Kuantan.”

(Sumber: Dr. R.G. Cant, 1973: |"An Historical Geography of Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 15-16).

Latar Sejarah Moden: Penemuan Bijih Timah

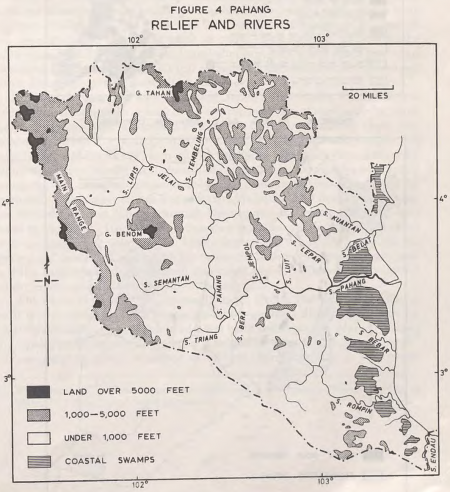

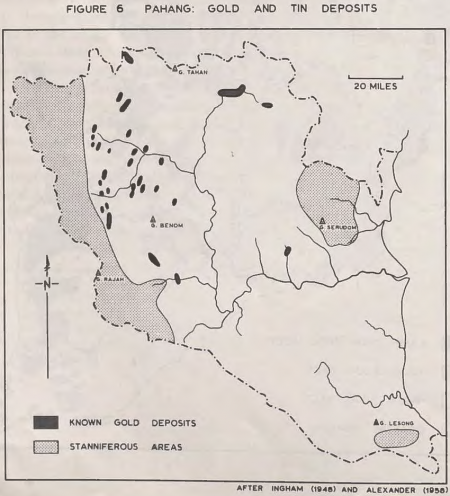

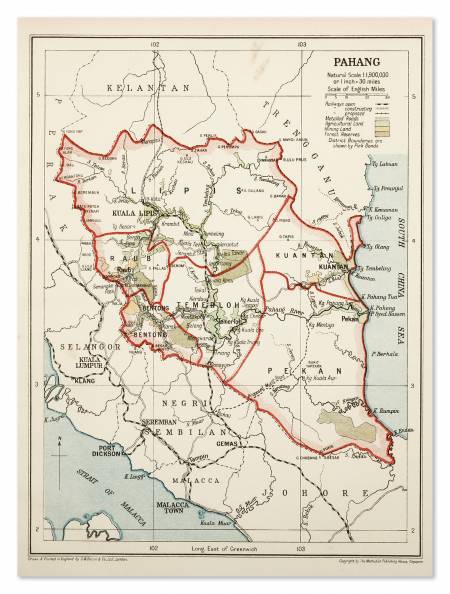

Kiri: “FIGURE 4 PAHANG RELIEF AND RIVERS”

Kanan: “FIGURE 6 PAHANG: GOLD AND TIN DEPOSITS”

“Pahang, in common with adjoining States of the Malay Peninsula, has mineral deposits which have Long attracted the attention of miners and traders. The present discussion is confined to minerals discovered prior to 1940. Tin has been found in three main areas of the State; firstly on the eastern slopes and margins of the Main Range; secondly on the flanks of Gunong Serudom in the Kuantan District; thirdly in the south of the State, in the vicinity of Gunong Lesong (fig. 6). Small quantities of gold have been discovered in many Localities, mainly within a broad belt known as the Malayan Gold Belt which extends from Mount Ophir in Johore, through Pahang into Kelantan, and north into Patani in Thailand. Iron ore exists in a number of places; in prehistoric times it was smelted in the valley of the Tembeling and in the 1930's large reserves were proved in south Pahang. Other minerals, such as copper, wolfram, and scheelite, have been mined in small quantities but they have never been important in the overall development of Pahang.” (Dr. R.G. Cant, 1973: |"An Historical Geography of Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 11).

1850-an: Pembukaan Kuantan

“Siapakah yang membuka, bilakah dibuka dan siapakah yang menamakan Kuantan tiada seorang pun yang dapat menentukannya. Melalui catatan sejarah, Kuantan telahpun wujud semenjak awal tahun 1850-an lagi. Kewujudan awal Kuantan pada kurun ke-19 bermula sebagai penempatan. Abdullah Munsyi pada 1851 @1852 menyentuh mengenai Kuantan seperti berikut :

'Hatta maka pada malam Khamis datanglah sebuah perahu kecil dari Kuantan. Maka berkhabarlah ia kepada anak-anak perahu mengatakan ada perahu lanun di Tanjung Tujuh, 40 buah dan di Pulau Kapas pun ada, dan di Pulau Badang pun ada, maka telah didapati dua buah perahu orang Kuantan dan dua buah perahu lepas lari'.

Menurut cerita lisan dari beberapa orang tua termasuk Tuan Kechik bin Tuan Abdullah, Batu Hitam, pada peringkat awalnya Kuantan lebih dikenali sebagai nama Kampung Teruntum. Penempatannya adalah di sekitarar Muara Sungai Teruntum, iaitu kawasan berhampiran hospital sekarang. Ia telah dibuka oleh Haji Senik dan pengikutnya sekitar tahun 1850-an.

Semasa tinggal di sini, mereka mengusahakan kawasan paya teruntum yang terletak di tapak hospital sekarang sehingga ke kawasan Sekolah Abdullah. Air daripada paya yang dikerjakan oleh mereka turun ke Sungai Besar (sekarang dikenali sebagai Sungai Kuantan) melalui Sungai Teruntum. Selain mengerjakan paya tersebut, mereka juga menangkap ikan dan berniaga secara kecil-kecilan. Bukti kawasan tersebut pernah dijadikan penempatan ialah terdapatnya perkuburan Cik Timah yang berhampiran Taman Esplanade.

(Cik Timah ialah anak Haji Senik yang telah disemadikan di tanah perkuburan tersebut. Apabila taman Esplanade diwujudkan di situ, ia melibatkan sebahagian daripada tanah perkuburan tersebut dan pusara Cik Timah telah dipindahkan ke Beserah bersebelahan pusara ayahnya Haji Senik dan ada sehingga hari ini…)

Berhubung dengan nama 'Kuantan', dikaitkan pula dengan pembukaan sebuah kawasan di hulu di Kampung Teruntum oleh orang Melayu dari daerah yang bernama Kuantan di Sumatera dengan diketuai oleh Encik Besar sekitar tahun 1854. Rombongan ini telah dibenarkan membuka kawasan tersebut. Orang yang datang kemudiannya telah memanggil tempat tersebut sebagai Kampung Orang Kuantan. Oleh sebab 'Kampung Orang Kuantan' itu terlalu panjang, maka dipendekkan dengan panggilan KUANTAN sahaja yang kekal sehingga ke hari ini.

Sumber : Dipetik dan diolah semula daripada monograf “PAHANG DALAM SEJARAH”, Lembaga Muzium Negeri Pahang, 1989.”

(Sumber: roshanilawatey, June 27, 2010: |"Sejarah Kuantan (1) : Jom Hebohkan...").

1833-1857: Pemerintahan Bendahara Tun Ali

“Mengikut Hikayat Pahang: pada masa pemerintahan Bendahara Tun Ali itu, negeri Pahang berada dalam keadaan aman dan makmur, barang dagangan murah, dua puluh gantang beras berharga hanya seringgit, rakyat dalam negeri ramai yang kaya, dalam negeri itu juga banyak didapati emas. Di lembahan Sungai Kuantan banyak didapati bijih timah dan dipunyai oleh Bendahara sendiri. Pada masa itu, barang yang keluar masuk di Pahang, kecuali di lembangan Sungai Kuantan, dikecualikan daripada cukai.” (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 128).

1836-05-23: Kelahiran Wan Ahmad

Salah seorang putera Tun Ali, Wan Ahmad (bakal pemerintah Pahang) telah dilahirkan: “Suratkhabar The Straits Times bertarikh 31 hari bulan 1875 ada menyebutkan: “Bendahara Wan Ahmad telah dilahirkan pada 5 hari bulan Muharam Tahun Hijrah 1252 (bersamaan dengan 23 hari bulan Mei 1836). Beliau berasal dari keturunan baka orang yang berumur panjang, bapanya Bendahara Ah dan moyangnya Bendahara Abdul Majid yang telah hidup hingga berumur lebih kurang lapan puluh tahun.” (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 212-213).

1856-05-25: Wasiat Tun Ali

“Pada 25 hari bulan Mei 1856, dan sekali lagi pada 15 hari bulan Oktober tahun itu juga (1856), Bendahara Tun Ali telah membuat surat wasiat menyebutkan: apabila ia meninggal dunia kelak, anaknya Tun Mutahir akan menggantikannya memerintah Pahang, tetapi hasil yang didapati dari daerah Kuantan dan daerah Endau, yang banyak mengeluarkan hasil bijih timah kepunyaan Bendahara itu, ditentukan terpulang kepada anaknya Wan Ahmad (Tun Ahmad).” (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 138).

1857: Tun Ali Mangkat, dan Wasiatnya Dikhianati

“1857. Setelah Bendahara Tun Ali meninggal dunia, beliau digantikan oleh anaknya Tun Mutahir yang telah lama memangku jawatan ayahnya itu, sebagai Bendahara pemerintah Pahang, bergelar Bendahara Seri Maharaja, disebut juga Bendahara Ganchong. Oleh sebab Bendahara Tun Mutahir tiada mengikut wasiat ayahnya yang telah menentukan hasil di daerah Kuantan, dan Endau diberikan kepada adiknya Wan Ahmad maka Wan Ahmad begitu marah dan hendak memberontak melawan abangnya.” (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 141).

1861-1863: Perang Saudara

1861 (April-Mei): Perang Endau

“Dalam bulan Mac 1861, Wan Ahmad yang telah menyiapkan orang dan kelengkapan perangnya di Kemaman, telah bergerak dari Kemaman hendak menyerang Pahang. … Angkatan perahu Wan Ahmad telah belayar menuju Kuala Pahang . Dalam pelayaran itu mereka telah membakar Kuantan. Kemudian mereka belayar lagi dan sampai di Sungai Miang, tiada berapa jauh di sebelah selatan kuala Sungai Pahang. Serangan pasukan Wan Ahmad di tempat itu tidak begitu memberi kesan. Oleh itu, mereka pun belayar lagi menuju Kuala Endau dan sampai di situ dalam bulan April 1861. Wan Ahmad telah bersatu dengan ketua Endau dan telah mendirikan kubu di Kuala Endau, dan menghantarkan juga dua buah perahu yang diketuai oleh Haji Abdul Rahman Kechau pergi ke Singapura untuk membeli senjata dan alat ubat bedil. Tiada berapa lama selepas itu, datanglah angkatan Bendahara Tun Mutahir dari Pekan sebanyak empat puluh buah perahu yang diketuai oleh Panglima Perang Mansu dari Kota, Panglima Kiri Encik Burok, Encik Embok, Encik Nit, Orang Kaya Syahbandar dan lain-lain datang menyerang pasukan Wan Ahmad di Kuala Endau. Angkatan Bendahara yang datang menyerang mengikut laut dibantu oleh satu pasukan yang datang melalui darat. Peperangan ini telah berpanjangan hingga bulan Mei 1861 peperangan itulah yang disebut oleh orang Melayu sebagai Perang Endau. … Pasukan Wan Ahmad telah dapat menguasai Endau dan beroleh rampasan beberapa buah peti besar berisi senjata ubat bedil dan bekalan makanan.”

1861 (Mei-Ogos): Perang Kuantan

“Tiada berapa lama selepas itu, dalam bulan Mei 1861 itu juga pasukan Wan Ahmad telah meninggalkan Endau belayar menuju ke Kuantan pula. … Pasukan Wan Ahmad telah berperang dengan pasukan Bendahara di Kuantan selama tiga bulan. Kesudahannya pasukan Wan Ahmad dikalahkan oleh pasukan Bendahara yang juga diketuai oleh Panglima Mansu. Pasukan Wan Ahmad telah terpaksa berundur meninggalkan Kuantan balik ke Terengganu dalam bulan Ogos 1861.”

1861 (Mei): Peralihan Kuasa Tun Mutahir - Wan Koris

“Semasa pasukan Wan Ahmad berperang dengan pasukan Bendahara di Endau dan di Kuantan (April-Ogos 1861), dalam bulan Mei itu juga, Bendahara Tun Mutahir telah memberitahu Gabenor Cavenagh di Singapura mengatakan ia telah menyerahkan pemerintahan negeri Pahang kepada anaknya Wan Koris (Wan Long).”

1861 (Ogos): Pemberontakan Wan Daud dan Khatib Rasu (Tok Gajah)

Bermulanya peranan Tok Gajah dalam sejarah Pahang, bersama Wan Ahmad. Ketika ini beliau dikenali sebagai Khatib Rasu (kemudiannya digelar “Imam Perang Rasu”), ketua orang Rawa dari Raub, yang bangkit menentang Tun Mutahir. Bersama mereka ialah orang Jelai di bawah pimpinan Wan Daud, yang ingin menuntut bela ke atas pembunuhan saudara mereka oleh orang-orang Tun Mutahir: “Pada 6 hari bulan Ogos 1861, Gabenor Cavenagh di Singapura telah menerima sepucuk surat daripada Bendahara Tun Mutahir yang memberitahu bahawa di Pahang masa itu sudah aman, tiada lagi pergaduhan. … Dalam bulan Ogos itu juga (1861), Wan Ahmad telah balik ke Terengganu setelah kalah dalam peperangan di Kuantan. Dan kedatangannya ke Terengganu masa itu tiada berapa dihormatkan oleh Sultan Terengganu, 'baginda itu kelihatan telah berubah sedikit'. Dengan itu Wan Ahmad pergi ke Kelantan dan berjumpa dengan Sultan Kelantan, Sultan Muhammad II (Sultan Mulut Merah) serta Raja Muda Kelantan… Beberapa hari selepas Wan Ahmad kalah di Kuantan, sekumpulan orang Melayu Rawa* dalam daerah Raub dan orang Jelai yang diketuai oleh Wan Daud bin Wan Pahang dan Khatib Rasu (kemudiannya terkenal dengan gelaran Tok Gajah) telah bangkit memberontak melawan Bendahara Pahang. Wan Daud ialah saudara sepupu kepada Wan Embong anak Maharaja Perba Jelai Wan Idris yang telah dibunuh oleh orang-orang Bendahara dalam tahun 1858 dahulu. Tujuan Wan Daud adalah sebagai membalas perbuatan Wan Aman yang zalim dan aniaya kepada orang-orang di Hulu Pahang dahulu. Tentangan dari pihak orang Wan Daud itu bukanlah mulanya dirancangkan untuk menyebelahi pihak Wan Ahmad walaupun kemudiannya pemberontakan itu memberi faedah dalam perjuangan Wan Ahmad melawan abangnya itu. Empat ratus orang Rawa telah masuk bersatu ke dalam pasukan yang melawan Bendahara Pahang. Di daerah Lipis, pasukan itu telah menangkap Tok Busu Dolah (Abdullah) anak Orang Kaya Temerloh. Kemudian, orang Rawa itu telah menawan Kuala Tembeling, dan di sinilah ketua mereka Khatib Rasu itu diberi gelaran Imam Perang.”

1861 (Disember): Perjanjian Pahang - Johor

“Dalam bulan Disember 1861, setelah dibenarkan oleh Kerajaan Inggeris, Temenggung Ibrahim bagi pihak kerajaan Johor telah membuat surat perjanjian dengan Bendahara Tun Mutahir bagi pihak kerajaan Pahang. Surat itu, bagi pihak Bendahara Pahang, telah ditandatangi oleh Wan Koris. Antara lain isi surat perjanjian itu menyebutkan: Johor dan Pahang berkerjasama antara satu dengan lain jika diserang musuh, jika timbul sebarang kekusutan antara mereka hendaklah diserahkan kepada kerajaan Inggeris sebagai orang tengah bagi menyelesaikannya, daerah yang terletak dari Endau ke Selidi Besar termasuk Pulau Tioman dan pulau-pulau di selatannya, dimasukkan ke dalam perintah kerajaan Johor.”

1862 (Ogos): Wan Ahmad Bersama Wan Daud dan Khatib / Imam Perang Rasu (Tok Gajah)

Di atas jemputan beberapa pembesar negeri Pahang (sebahagiannya berpaling tadah daripada Tun Mutahir), Wan Muda kembali ke Terengganu untuk bersiap menyerang Pahang sekali lagi: “Apabila Wan Ahmad menerima jemputan itu beliau pun menyegerakan persiapannya untuk menyerang Pahang. Apabila semua kelengkapannya telah siap, berangkatlah Wan Ahmad ke Kuala Terengganu mengadap Sultan Terengganu (Baginda Umar) yang telah memberikan wang perbelanjaan dan senjata kepada Wan Ahmad. Peristiwa ini telah berlaku dalam bulan Jun atau julai 1862. … Dari Terengganu, Wan Ahmad membawa pasukan perangnya menuju ke Paliang. Angkatan perang Wan Ahmad itu telah melalui sempadan negeri Paliang di Bukit Busut dalam bulan Ogos 1862. Apabila sampai di Janing, di Hulu Tembeling (Hulu Pahang), beribu-ibu orang Pahang yang menyebelahinya telah menanti dan menyambut kedatangan Wan Ahmad. Kemudian Wan Ahmad menghilir lagi, tatkala melalui jeram di situ, beberapa buah rakit orang-orang Wan Ahmad telah terbalik dan telah kehilangan beberapa buah senjata dan peluru tetapi pelayaran itu diteruskan juga hingga sampai ke hilir Tambang di Kuala Tembeling. Di sini Wan Ahmad telah disambut dengan gembiranya oleh pasukan orang Rawa, Jelai dan Lipis yang diketuai oleh Tok Raja, Wan Daud, Panglima Perang Wan Muhammad, Imam Perang Rasu, Orang Kayu Lipis dan ramai lagi. Pada masa itu mereka telah dapat khabar mengatakan kubu pasukan pihak Bendahara yang di Kangsa itu telah di tinggalkan dan pasukan Bendahara itu telah berkubu semula di Chenor. … Pasukan Wan Ahmad telah menyerang Chenor dan beberapa tempat perkubuan pihak Bendahara. … Dalam peperangan itu, pihak Bendahara telah dapat dikalahkan. Wan Ahmad telah dapat menduduki Chenor. Haji Hasan dan anak-anaknya masuk menyebelahi pihak Wan Ahmad. Wan Aman adik Wan Koris dengan segera meninggalkan Chenor dan kembali ke Pekan. … Pasukan Wan Ahmad terus mara sampai ke Sungai Duri. … Pihak Bendahara telah menghantar satu pasukan baharu … pergi menanti pasukan Wan Ahmad di Pulau Lebak (di Sungai Pahang). … Pasukan Wan Ahmad telah datang menyerang tempat itu, setelah bertempur, pihak Bendahara dapat dikalahkan dan berundur dari situ, bertahan dan berkubu pula di tempat yang bernama Pulau Kepayang. Tiga bulan lamanya pihak Bendahara berkubu di Pulau Kepayang melawan Wan Ahmad. Akhirnya mereka dapat dikalahkan oleh pasukan Wan Ahmad dan lari meninggalkan Pulau Kepayang, pergi ke Pulau Manis, dari sini berundur lagi ke tempat yang bernama Temai, dan di sini juga peperangan berlaku di antara kedua belah pihak. … Pasukan Wan Ahmad telah dipecahkan kepada dua bahagian, sebahagian diketuai oleh Wan Ahmad sendiri serta Tok Raja (Maharaja Perba Jelai) pergi membantu pasukannya di-Kuala Bera. Sebahagian lagi tinggal untuk melawan pihak Bendahara di Temai di bawah pimpinan beberapa orang hulubalang Wan Ahmad yang gagah, di antaranya termasuk Imam Perang Rasu, Wan Daud, Orang Kaya Lipis, Imam Perang Jambang (orang Rawa) dan ramai lagi. … Peperangan di Temai itu berjalan terus hingga memasuki tahun 1863.”

1863 (10 Jun): Kemenangan Wan Ahmad

“1863. Wan Ahmad telah mengatur semula pasukannya dan telah menetapkan azam hendak melanggar Pekan dengan mengejut. Pengikutnya itu, selain daripada yang tinggal meneruskan peperangan di Temai, telah dipecahkan kepada tiga pasukan, tiap pasukan mengandungi lebih kurang enam ratus orang, di bawah pimpinan Imam Perang Raja, Imam Perang Rasu, Panglima Raja, Panglima Kakap Bahaman dan Tuan Embong. Setiap pasukan ditetapkan untuk melanggar satu tempat yang telah ditentukan, iaitu satu pasukan akan melanggar pasukan pihak Bendahara yang berkubu di Tanjung Parit, satu pasukan lagi yang diketuai oleh Imam Perang Rasu akan melanggar kubu di Kampung Masjid, dan satu pasukan yang mengandungi orang Jelai akan melanggar Kampung Baharu. … Setelah Pekan dapat ditawan oleh Wan Ahmad, Bendahara Tun Mutahir dan anak-anaknya serta pengikutnya telah berundur ke Kampung Syahbandar yang bernama Kampung Jambu. Pengikut Bendahara di Kampung Jambu dan di Pekan Seberang telah juga diserang oleh pihak Wan Ahmad. Bendahara dan pengikutnya telah lari menghilir Sungai Pahang dan bersembunyi di Tanjung Teja dekat kuala Sungai Pahang. Orang-orang Bendahara di Temai, setelah lima bulan lamanya berperang, akhirnya telah dikalahkan juga oleh pihak Wan Ahmad. … Dalam bulan Mei 1863, Bendahara Tun Mutahir yang telah uzur itu bersama dengan anaknya Wan Koris serta pengikut mereka dalam satu angkatan telah bertolak dari Tanjung Teja meninggalkan Pahang menuju ke Johor. Dengan tiada disangka, ketika sampai di Kuala Pahang, Wan Koris telah meninggal dunia tetapi pelayaran angkatan itu diteruskan juga membawa jenazah almarhum itu. Sampai di Kuala Sedili, Bendahara Tun Mutahir pula mangkat. Kedua-dua jenazah itu dibawa terus oleh angkatannya ke bandar Tanjung Puteri (Johor Baharu sekarang) dan dimakamkan di situ. Pada 10 hari bulan Jun 1863, Wan Ahmad telah berjaya mengambil Pahang dari tangan abangnya almarhum Bendahara Tun Mutahir. Oleh sebab itu orang-orang besar Pahang telah mengangkat Wan Ahmad menjadi Bendahara, raja pemerintah Pahang bergelar Bendahara Siwa Raja (Seri Wak Raja).”

(Sumber: Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 157-176).

Kesan Perang Saudara

“On the eve of British administration the population of Pahang was predominantly Malay. Europeans had not entered the State in any numbers and the Chinese population was much smaller than it had been four decades earlier. The aboriginal peoples, the Senoi and the Jakun, were largely hidden away in the forested interior. The Chinese had dwindled in numbers during the period of widespread lawlessness that began with the death of Bendahara Ali in 1857. Many of the Chinese miners or traders were either murdered or driven out, and as new arrivals from China were attracted to the more developed west coast States, there were only an estimated two to three hundred Chinese in Pahang when Swettenham visited the State in 1885.” (Dr. R.G. Cant, 1973: |"An Historical Geography of Pahang" (PDF),m.s.31).

1863-1873: Awal Pemerintahan Wan Ahmad

1863 (Oktober): Tuntutan Sempadan dan Kepulauan

“Wan Daud digelar Maharaja Setia Raja diberi kuasa memerintah lembahan Sungai Lipis iaitu dari kuala Sungai Lipis sampai ke hulu sungai itu. Ketika itu juga Bendahara Wan Ahmad mengeluarkan perintah semua barang dagangan yang dibawa keluar masuk tiada dikenakan cukai selama tiga tahun, kecuali di Kuantan kerana daerah itu telah dikhaskan kepunyaannya sendiri. … Sejak Bendahara Wan Ahmad menjadi raja pemerintah di Pahang, tiada lagi berlaku perkelahian bersenjata di antara pihak Bendahara dengan pihak Temenggung Abu Bakar Johor, dalam pada itu, Bendahara Pahang dengan Temenggung Johor itu masih juga berselisih faham mengenai pulau-pulau di Laut Cina Selatan yang telah diserahkan oleh almarhum Bendahara Tun Mutahir kepada kerajaan Johor dahulu dan tiada disetujui oleh Bendahara Wan Ahmad demikian juga berkenaan dengan sempadan negeri mereka. Bendahara Wan Ahmad tetap mengatakan Pulau Tioman, Pulau Tinggi, Pulau Aur dan pulau-pulau lain adalah termasuk dalam kuasa kerajaan Pahang. Dalam bulan Oktober 1863 itu juga, Bendahara Wan Ahmad telah memanggil ketua-ketua di Pulau Tinggi, Pulau Tioman dan Pulau Aur datang berkumpul berjumpa Bendahara di Mersing dan Bendahara telah dapat pengakuan yang menyatakan mereka tetap taat setia kepada Bendahara Pahang.”

1868 (1 September): Pengiktirafan Johor dan British

“Perselisihan di antara Bendahara Wan Ahmad dengan Temenggung Abu Bakar belum juga selesai. Tetapi dalam tahun 1867 ini, tiada berapa lama sebelum Gabenor Sir Harry Ord sampai di Singapura menjadi Gabenor Negeri Selat menggantikan Cavenagh, Temenggung Abu Bakar telah bersetuju hendak menyerahkan Pulau Tioman, Pulau Seri Buat, Pulau Kaban dan pulau-pulau lain yang terletak di sebelah utara Garisan Lintang 20 40' kepada kerajaan Pahang (Bendahara Wan Ahmad) untuk menyelesaikan perselisihan yang telah begitu lama berlanjutan. Pada tahun 1867 itu juga, Sir Harry Ord telah sampai di Singapura menggantikan Orfeur Cavenagh menjadi Gabenor Negeri Selat. Gabenor Harry Ord telah mengambil tindakan untuk merundingkan hal perselisihan di antara Johor dengan Pahang itu. Pada bulan Ogos 1868, dalam lawatannya ke pantai timur Semenanjung Tanah Melayu, Gabenor Harry Ord telah singgah di Pekan (Pahang) berjumpa Bendahara Wan Ahmad dan merundingkan perkara tersebut. Pada masa itu, telah ditetapkan Sungai Endau menjadi sempadan di darat antara negeri Pahang dengan negeri Johor, dan ke lautnya, dari tengah kuala Sungai Endau mengikut satu garisan lintang yang dijangkakan dari situ lurus arah ke timur, laut dan pulau yang terletaknya di sebelah utara daripada garisan lintang itu, masuk ke dalam perintah Pahang, Pulau Tioman masuk ke dalam perintah Pahang, dan laut serta pulau yang terletak di sebelah selatan daripada garisan lintang itu masuk perintah Johor. Pada 1 hari bulan September 1868 telah ditandatangani surat perjanjian mengenai keputusan itu oleh Bendahara Wan Ahmad bagi pihak kerajaan Pahang, dan Maharaja Abu Bakar* bagi pihak kerajaan Johor dengan disaksikan oleh Gabenor Harry Ord. Sejak itulah juga kerajaan British mula mengakui Bendahara Wan Ahmad sebagai raja pemerintah Pahang. Pada tahun 1868 itu juga, Wan Da anak almarhum Bendahara Tun Mutahir yang dibantu oleh Sayid Deraman (Abdul Rahman), Imam Perang Mat Aris dan Tuan Kechut serta orang Rawa telah menyerang Raub (di Pahang). Bendahara Wan Ahmad telah menghantar pasukan perangnya dari Pekan pergi melawan pasukan yang menyerang itu. Pasukan Bendahara diketuai oleh Haji Muhammad Nur bin Haji Abdul Hamid, seorang orang besar di Pekan, Orang Kaya Lipis, Imam Perang Rasu, Tok Kali Sega dan Tok Mamat Budu. Pertempuran di antara kedua-dua belah pihak telah berlaku di tempat yang bernama Saga. Imam Perang Wan Muhammad anak Maharaja Perba Jelai Wan Idris, yang membawa pasukannya orang Jelai telah datang membantu pasukan Bendahara Wan Ahmad. Setelah bertempur selama lima hari, akhirnya pihak Wan Da dapat dikalahkan dan lari ke Selangor.”

1870-1873: Khatib / Imam Perang Rasu (Tok Gajah) dan Perang Selangor

Semenjak itu bermula penglibatan tokoh-tokoh Selangor dan Pahang di dalam perebutan kuasa masing-masing. Setelah 4 tahun peperangan (1870-1873), akhirnya Tengku Kudin (disokong oleh Wan Ahmad melalui Khatib / Imam Perang Rasu) berjaya mengalahkan Raja Mahadi (disokong oleh Wan Aman, Wan Da, dan Raja Asal), dan Khatib / Imam Perang Rasu dianugerahi Pulau Tawar di Jerantut, dengan gelaran “Orang Kaya Imam Perang Indera Gajah” atau “Tok Gajah”: “Setelah Kuala Lumpur ditawan semula oleh Tengku Kudin, Imam Perang Rasu serta beberapa orang pengiringnya balik semula ke Pahang dengan penuh gembira kerana kemenangan mereka di Selangor itu. Orang Kaya Pahlawan Semantan (Datuk Bahaman) dengan beberapa orang askar Pahang tinggal menjaga Hulu Kelang. Sejak itu hingga awal bulan November 1873 boleh dikatakan tiada berlake peperangan di Selangor. Apabila sampai di Pahang, oleh sebab jasanya dalam peperangan itu Bendahara Wan Ahmad telah mengurniakan gelaran kepada Imam Perang Rasu “Orang Kaya Imam Perang Indera Gajah”, dan pembantunya Encik Gendut Imam Perang Raja telah dinaikkan pangkat dan digelar “Imam Perang Indera Mahkota”. Tempat yang bernama Pulau Tawar dekat Jerantut telah dikurniakan oleh Bendahara Wan Ahmad menjadi hak milik Orang Kaya Imam Perang Indera Gajah (Khatib Rasu). Beliau itu biasanya disebut Tok Gajah sahaja.”

(Sumber: Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 178-187).

1863-1889: Penempa Duit Tampang

“Dalam tahun 1847, duit tampang yang berharga satu sen telah diadakan di Pahang. Setelah Bendahara Wan Ahmad menakluki Pahang pada tahun 1863, Datuk Bendahara itu telah mengumpulkan semula beberapa banyak wang tampang satu sen itu, dilebur dan ditempa menjadi kepingan tampang yang lebih kecil dan lebih buruk keadaannya. Dalam tahun 1889, kerajaan Pahang telah mengisytiharkan iaitu duit tampang yang diedarkan oleh Sultan Pahang mulai 1 hari bulan Julai 1889 hendaklah diakui sah pembayarannya tetapi duit tampang itu tidak akan dikeluarkan lagi. Peraturan menggunakan duit tampang di Pahang telah diberhentikan dalam tahun 1893. Pekerjaan menempa duit tampang di Pahang dikhaskan oleh kerajaan Pahang kepada orang Cina, di mana diperintahkan menempa duit itu empat kali dalam setahun dan ditetapkan pula berapa banyak yang hendak dibuat. Tempat menempa duit tampang itu ialah di Kuantan, di Lepar, di Semantan dan di Pekan Lama. Semasa dalam pemerintahan Bendahara Wan Ahmad, baginda telah membenarkan acuan menempa tampang itu disimpan dalam penjagaan orang besar Pahang yang bergelar Imam Perang Indera Mahkota dan Orang Kaya Bakti (seorang India).” (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 134).

1880-an: Padi Huma dan Hasil Hutan

Tinjauan pada tahun 1880-an mendapati kawasan tanaman padi huma di sepanjang Sungai Kuantan, tapi tidak sebanyak di sepanjang Sungai Pahang di daerah Pekan:-

“In the 1880's the Malay subsistence economy had broken down to a much greater extent than some contemporary writers realised. Daly and Skinner, for example, both believed that agriculture in Pahang was well developed and productive by the Malay standards of the time. … In the Pekan District there were flat alluvial tracts along the Pahang River which could be used for tenggala cultivation but ladang methods were most popular both here and along the more sparsely settled Kuantan River. The swamp margins were occasionally planted with wet padi. In the few localities where coastal settlers did attempt to grow crops ladang cultivation, with fresh clearings made every year or two years, was the normal method of production.” (Dr. R.G. Cant, 1973: |"An Historical Geography of Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 34-36).

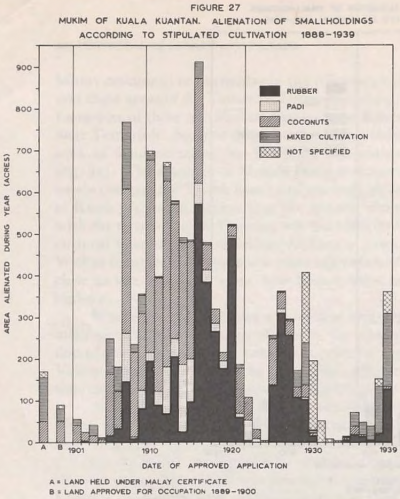

“Behind the river banks of the coast districts there was paya land which could be used for wet padi cultivation but any such tradition was lacking except in some of the kampongs adjacent to the Pahang River and in the Luit valley. District Officers at both Kuan tan and Pekan worked hard to encourage the growth of wet padi and the improvement of other forms of cultivation. At Kuantan the counter-attractions were too strong; there was no alienation of wet padi land and little increase in the number of holdings taken up for other forms of subsistence agriculture (fig. 27). Immigrant Malays familiar with wet rice cultivation showed no inclination to develop it in east Pahang and the local Malays preferred to grow dry rice or collect jungle produce.” (Dr. R.G. Cant, 1973: |"An Historical Geography of Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 58-59).

Selain itu, hasil hutan dari kawasan pedalaman Sungai Kuantan dibawa ke Kuala Kuantan untuk dieksport ke Singapura, Kelantan dan Terengganu: “In 1888 the forest was also the source of a cash income. With Singapore established as a major trading centre there was a considerable demand for jungle produce and timber. In those areas of Pahang adjacent to existing settlements the local Malays and the Aborigines worked spasmodically to collect forest produce for sale as well as for subsistence. … Atap and Mengkuang were collected mainly for local markets and exported to Kelantan and Trengganu, while quantities of guttas, rattans, bamboos, and damar torches were sent to Singapore. Timber was exported in the form of baulks or planks, Chengal from the Kuantan District was in great demand in Trengganu for boats and houses and Chinese junks en route to China frequently called at Kuantan to complete their cargoes with quantities of coffin wood. Most of the timber exported, however, went to the Singapore market.” (Dr. R.G. Cant, 1973: |"An Historical Geography of Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 39-40).

1880-1900-an: Awal Perlombongan Moden

Ringkasan era awal perlombongan moden di sekitar Kuantan:-

“Semenjak pembukaannya pada pertengahan kurun ke-19, Kuantan terus berkembang walaupun perkembangannya tidak begitu pesat. Jangka masa antara 1860 – 1970 perkembangannya dan pembangunan Kuantan telah dipengaruhi oleh beberapa faktor, iaitu :

1. Pusat pengeluaran dan pengumpulan hasil bijih timah dan lain-lain bahan mentah.

2. Pemodenan dan perubahan dasar-dasar pentadbiran

3. Sistem perhubungan dan pengangkutan

4. Kemudahan pendidikan

Kuantan mula membangun apabila hasil bijih timah dijumpai di kawasan Sungai Lembing dan Gambang. Perlombongan bijih timah di Sungai Lembing telah diusahakan semenjak zaman pra sejarah lagi. Namun, tiada perlombongan secara intensif dijalankan sehinggalah pada abad ke-19 apabila kaum bumiputera dan Cina meningkatkan aktiviti mereka di kawasan-kawasan perlombongan tersebut. Kawasan perlombongan bijih timah di Gambang telah dibuka oleh kaum Cina pada awal tahun 1880-an sementara kawasan perlombongan Sungai Lembing pula dalam tahun 1868 oleh Lim Ah Sam dan kemudiannya diusahakan secara intensif oleh Syarikat “The Pahang Corporation Limited” pada tahun 1887.

…

Hasil bijih timah dari Gambang dibawa ke Kuantan melalui Sungai Belat di Gudang Rasau, manakala hasil dari Sungai Lembing pula dibawa ke Pasir Kemudi dengan trak (kereta api) dan kemudiannya diangkut dengan kapal wap (belangkas) ke Kuantan untuk dieksport melalui Pelabuhan Kuantan.

Bagi memenuhi keperluan aktiviti ini, beberapa kawasan di pinggir Sungai Kuantan telah dimajukan sebagai pusat pengurusan dan pengumpulan bahan mentah, seperti bijih timah. Di antaranya ialah kemudahan pelabuhan, pejabat kastam, pejabat pentadbiran daerah, kedai dan sebagainya yang terletak di kawasan sekitar Jalan Besar, Jalan Mahkota dan Pinggir Sungai Kuantan.

Dengan corak pembangunan ini, kawasan bandar mula didiami oleh orang-orang Cina, sementara orang Melayu yang mula membuka penempatan awal di tebing Sungai Kuantan telah berpindah ke kawasan pinggir bandar, seperti di Padang Lalang, Tanjung Lumpur, Beserah, TANAH PUTIH, dan sebagainya.”

(Sumber: roshanilawatey, 2010: |"Sejarah Kuantan (2) : Pusat Pengumpulan Hasil Bijih Timah").

1883-11-08: Perlombongan Lim Ah Sam

Lim Ah Sam, seorang hartawan Cina yang tinggal di Pulau Belitong, telah dianugerahi konsesi beberapa bidang tanah di Pahang termasuk Sungai Kuantan:-

- “Dalam bulan November 1883 itu juga, Sultan Ahmad Pahang telah memajakkan satu kawasan tanah di Pahang seluas 2,000 batu persegi untuk membuka lombong dan pertanian kepada Lim Ah Sam seorang hartawan Cina yang tinggal di Pulau Belitong dan mempunyai perniagaan di Singapura. Juga kepada seorang Cina Singapura bernama Goh Swee Sui yang telah banyak mengeluarkan wangnya dalam perusahaan melombong bijih timah di Perak dan seorang Eropah bernama Louis de Dekker dan seorang Cina lagi bernama Ho Ah Yun.” (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 222).

- “The Ulu Kuantan territory of Sungei Lembing at that time was deemed to be the private domain of the Sultan of Pahang. The story has it that on his marriage with the daughter of Lim Assam (Ah Sam) known as Captain China of Billiton he gave this land to his wife as a wedding present, and she in turn passed the mining rights on to her father. Under a Concession dated November 8, 1883, the land of “Sunghai Kuantan, Sunghai Triang, Sunghai Rumpen and Sunghai Endau”, an area of 2,500 square miles, was granted for 75 years to the Pahang Company, a company to be formed by “Towkay Lim Assam of Billiton, Towkay Goo Soo Sooee of Singapore and Mr. Louis den Dekker, gentleman, residing in Singapore. Under the terms of the Concession a royalty of 10 per cent on all tin or other minerals exported was to be paid, but the company was to be exempted from all port dues and other kinds of duty, including that on timber, which the company was to be allowed to cut in any part of Pahang.” (Pahang Consolidated Company, 1966: |"Sixty Years of Tin Mining: A History of The Pahang Consolidated Company - 1906-1966: I. The Pioneering Years - The Pahang Corporation" (PDF), m.s. 12)

1884-12-12: Pertabalan Sultan Ahmad Al-Muazzam Shah

“Pada 6 hari bulan Ogos 1882, Bendahara Wan Ahmad mula memakai gelaran Sultan - Sultan Pahang.” (m.s. 219).

“Pada 12 hari bulan Disember 1884, dalam satu istiadat besar yang telah diadakan di Pekan (Pahang), orang-orang besar Pahang telah menabalkan Sultan Ahmad sebagai Sultan Pahang dengan gelaran Sultan Ahmad Al-Muazzam Shah, bagindalah keturunan Bendahara kerajaan Johor-Riau-Lingga-Pahang dahulu yang pertama memakai gelaran Sultan di Pahang. Pada masa itu baharulah gelaran itu diisytiharkan kepada semua rakyat di seluruh negeri Pahang. Isteri baginda Tun Besar yang bergelar Cik Puan Bongsu (bonda Tun Long) digelar Tengku Ampuan Pahang. Anak-anak baginda yang dahulunya dipanggil Tun diubah kepada Tengku. Sepupu baginda yang bernama Wan Abdul Rahman disebut juga Engku Ngah (anak Tun Muhammad Engku Tanjung) dilantik menjadi Bendahara, anak saudara baginda yang bernama Wan Mahmud (anak Wan Ismail) diingkat menjadi Temenggung bergelar Temenggung Seri Maharaja.” (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 230).

1887-10-08: Perjanjian British, melalui Hugh Clifford

Semenjak awal pemerintahan Bendahara (kini Sultan) Wan Ahmad lagi, pihak British melalui wakilnya Hugh Clifford, telah membuat beberapa percubaan perlantikan wakilnya di Pahang. Akhirnya, berikutan beberapa konflik dalaman yang dihadapi oleh Sultan Ahmad (antaranya perselisihan dengan adiknya sendiri Wan Mansur), dorongan daripada wakil Sultan Abu Bakar Johor, serta pengaruh para pemodal hartawan, beliau akhirnya bersetuju melantik wakil British, pada 8 Oktober 1887. Hugh Clifford kemudiannya dilantik sebagai wakil British di Pahang: “Akhirnya, pada 8 hari bulan Oktober 1887 (bersamaan dengan 20 hari bulan Muharam Tahun Hijrah 1305), Sultan Ahmad bagi pihak kerajaan Pahang telah menandatangani surat perjanjian dengan kerajaan British. Sebagai menghormati peristiwa menandatangani surat perjanjian itu, bendera British telah dikibarkan di Pekan dan diikuti dengan tembakan meriam 21 das. Esoknya, pada 9 hari bulan Oktober 1887, surat perjanjian yang telah ditandatangani oleh Sultan Ahmad itu dibawa ke Singapura untuk ditandatangani oleh Gabenor Sir Frederick Weld bagi pihak kerajaan British. Sejak itu (tahun 1887) baharulah kerajaan British mengakui gelaran Sultan yang telah dipakai oleh Sultan Ahmad sejak dari tahun 1882 dahulu. Dan Gabenor Weld telah melantik Hugh Clifford menjadi wakil British di Pahang.” (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 258).

Pada akhir bulan April 1888, Hugh Clifford membuat lawatan ke segenap pelusuk negeri untuk meninjau keadaannya. Di Pulau Tawar (daerah Tok Gajah), beliau berjumpa dengan kedua-dua anak Tok Gajah, iaitu Mat Kilau dan Awang Nong: “Pada akhir bulan April 1888, Hugh Clifford telah bertolak dari Pekan pergi melawat ke merata tempat di Pahang … Di Pulau Tawar, Clifford telah berjumpa dengan dua orang anak lelaki Tok Gajah yang bernama Mat Kilau dan Awang Nong, dan Qifford telah bersahabat dengan mereka.” (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 267-270).

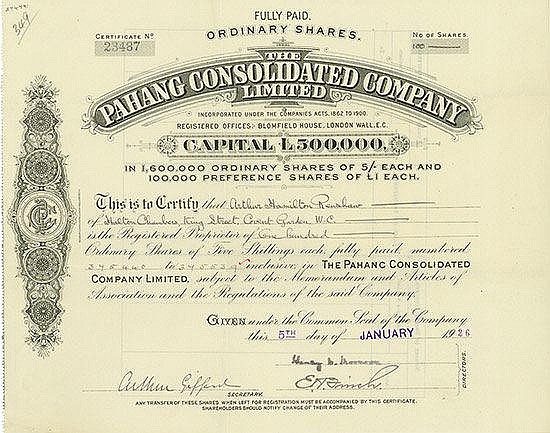

1888-09-01: The Pahang Corporation Limited

Pada mulanya, Sultan Ahmad telah membatalkan pemajakan tanah lombong di Kuantan yang dianugerahkan kepada syarikat William Paterson oleh abangnya Tun Mutahir dahulu: “Dalam bulan Disember 1887 itu juga, Sultan Ahmad telah membatalkan (memberhentikan) kebenaran pemajakan sebuah syarikat British di daerah Kuantan yang asalnya telah diberikan oleh almarhum Bendahara Tun Mutahir kepada William Paterson seorang saudagar British di Singapura dalam tahun 1862 dahulu. Dalam tahun 1887 ini, William Fraser bagi pihak syarikat telah diberi peluang supaya menjelaskan wang sebanyak $30,000/- kepada Sultan Pahang dan telah diberi tempoh untuk membuka kawasan pemajakan itu. Tetapi oleh sebab wang tersebut tidak dijelaskan dan tempohnya juga sudah tamat, kebenaran pemajakan di daerah Kuantan kepada syarikat itu pun dibatalkan oleh Sultan Ahmad. Tetapi perkara itu telah berlarutan sampai ke tahun 1888 dan telah membabitkan Pejabat Tanah Jajahan British di London dan juga Gabenor di Singapura.” (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 284).

Pihak kerajaan British berkepentingan besar di dalam syarikat ini, lalu mengambil peranan utama dalam usaha menyelesaikan masalah ini: “Berkenaan dengan kebenaran pemajakan kepada syarikat orang British di daerah Kuantan yang telah dibatalkan oleh Sultan Ahmad dalam bulan Disember 1887 dahulu, tidaklah diketahui oleh pengarah syarikat itu di London apakah sebab yang sebenarnya sehingga pembatalan itu dilakukan oleh baginda kerana wang sebanyak $30,000/- yang dikehendaki oleh kerajaan Pahang, serta tempoh yang telah diberikan untuk membuka tanah pajak itu, tidak diberitahu oleh William Fraser kepada pengarah syarikat itu. Oleh sebab itu dalam bulan April 1888 N.S. Maskelyne seorang daripada pengarah syarikat itu dan juga seorang ahli Parlimen British, telah mengadu kepada Setiausaha Pejabat Tanah Jajahan British di London dan telah memberikan penerangan mengenai kedudukan syarikatnya di Kuantan, dan ia telah juga meminta Setiausaha Pejabat Tanah Jajahan British membantu mentadbir syarikatnya di Pahang dan menahan supaya Sultan Pahang jangan membatalkan kebenaran pemajakan syarikatnya, dimintanya juga supaya Setiausaha Tanah Jajahan British itu menggunakan pengaruh kerajaan British dengan memberi cadangan menerusi wakil British yang ada di Pahang dari faedah syarikatnya. Setiausaha Pejabat Tanah Jajahan British percaya syarikat itu adalah sebuah syarikat yang baik dan patut ditolong dan beliau telah mengutus surat kepada Gabenor di Singapura supaya Gabenor mengadakan satu ketetapan yang difikirkannya baik bagi faedah syarikat itu. Akhirnya, pada awal bulan September 1888 itu juga, syarikat itu telah mendapat kebenaran pemajakan yang baharu dan yang lebih baik diberi oleh Sultan Pahang.” (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 269).

Akhirnya, konsesi perlombongan di sepanjang Sungai Kuantan (termasuk Sungai Gambang dan cabang-cabangnya) seluas 2,000 batu persegi selama 80 tahun dianugerahkan kepada syarikat “The Pahang Corporation Limited”, melalui wakil syarikat asal, Mr. William Fraser: “In 1887, a new company was formed in England, The Pahang Corporation Limited, and registered on December 3 of that year. Again through the instigation of William Fraser and because the Corporation proposed “to do business on a larger scale” , the Sultan Ahmad Muatham Shah of Pahang, granted a new Concession. This Concession, dated September 1, 1888, for 80 years, comprised some 2,000 square miles of largely unsurveyed land, and excluded the Sungei Triang area but added the valleys of the Sungei Gambang and its tributaries. William Fraser became the Corporation's Local Director. The same royalty of 10 per cent was payable under the new Concession on tin and certain other minerals, but other rates were quoted for copper, lead, tapioca, coffee, pepper and gambier. Almost immediately, the Corporation, with an issued capital of no more than £200,000, appreciated that the immense area of land possessed by it could only be adequately worked with large capital, and sub-leased two portions for £100,000 each to The Pahang-Kabang Ltd. and The Pahang-Semeliang Co., subsidiary companies.” (Pahang Consolidated Company, 1966: |"Sixty Years of Tin Mining: A History of The Pahang Consolidated Company - 1906-1966: I. The Pioneering Years - The Pahang Corporation" (PDF), m.s. 13).

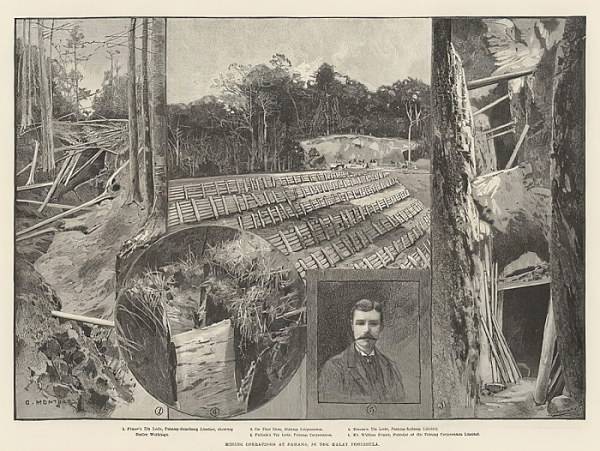

Mr. William Fraser dan lombong-lombong awal Pahang Corporation (1890): 1 (Kiri): “Fraser's Tin Lode, Pahang Semiliang Limited Native Workings”. 2 (Atas): “Thai Dam, Pahang Corporation”. 3 (Kanan): “Pollock's Tin Lode”. 4 (Bawah kiri): “Simons's Tin Lode, Pahang Kabang Limited”. 5 (Bawah kanan): “Mr William Fraser, Founder of the Pahang Corporation Limited”. (Charles Auguste Loye / George Montbard, 1890: |"Mining in Pahang, on the Malay Peninsula").

NOTA: Mr. William Fraser kemungkinan berasal dari Scotland, dan pernah menyumbang dalam percetakan sebuah buku puisi Gaelic: The cost of illustration (Dàin agus Orain Ghàidhlig, 1891) was defrayed by William Fraser of Pahang…” (Anne Loughran, 2018: |"Gaelic Literature of the Isle of Skye: an annotated bibliography").

1888-10: Perlantikan Residen British, J.P. Rodger

Syarikat Pahang Corporation Limited ini terus menjadi kepentingan utama pihak pentadbir British di Pahang. Mereka terus berusaha untuk mendapat persetujuan Sultan Ahmad bagi perlantikan residennya di Pahang, bagi memastikan kepentingan ini dapat terus dijaga dan dimanfaatkan. Usaha ini akhirnya berhasil pada Oktober 1888, dengan perlantikan J.P. Rodger sebagai Residen Pahang yang pertama: “Dalam bulan Oktober 1888 itu juga kerajaan British telah melantik seorang pegawainya bernama J.P. Rodger menjadi Residen British yang pertama di negeri Pahang. Tetapi pada hari bulan Julai 1889 baharulah ia datang ke Pahang memegang jawatannya itu. Sejarah mengenai Pahang yang telah ditulis oleh orang Barat berkenaan dengan kerajaan British meletakkan Residennya menggantikan wakil British di Pahang itu, terutama sebabnya yang telah dihebahkan oleh mereka ialah kerana pembunuhan yang telah berlaku terhadap seorang Cina rakyat British di negeri itu. Tetapi jika diperhatikan daripada kisah yang telah disebutkan di atas itu nyata sebabnya bukanlah kerana pembunuhan itu sahaja, melainkan terutamanya ialah kerana muslihat hendak memelihara kepentingan saudagar British yang telah menanam modal dalam syarikat yang menjalankan perusahaan melombong emas dan bijih timah di Pahang terutama syarikat British bernama Pahang Corporation Limited yang mendapat sokongan dari Pejabat Tanah Jajahan British di London.” (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 276).

1889-07-01: J.P. Rodger Mula Bertugas

“Pada 1 hari bulan Julai 1889, J.P. Rodger mula menjalankan tugas-tugasnya sebagai Residen British yang pertama di Paliang, dan tinggal di Pekan. Pada masa itu (tahun 1889) telah dilantik beberapa orang pegawai British memegang jawatan pentadbir dalam beberapa buah daerah di Pahang dengan gelaran Pemungut Cukai dan Majistret (Collector and Magistrate) yang berkuasa sebagai pegawai daerah pada masa ini, dan mereka jugalah yang menguasai pasukan polis di daerah masing-masing. Pegawai British yang pertama memegang jawatan pentadbir di Pahang itu ialah F. Belfield di Pekan, W.W. Michell di Kuala Pahang, A.H. Wall di Kuantan, E.A. Wise di Temerloh, dan W.C. Michell di Pahang. Pada masa itu Hugh Clifford yang telah diangkat menjadi Penguasa di Hulu Pahang (Superintendent of Hulu Pahang) telah pergi bercuti, dan jawatannya dipegang oleh W.C. Michell. Pegawai British itu telah diarahkan oleh kerajaan British supaya berikhtiar mendapatkan kerjasama orang-orang besar Pahang bagi menjalankan pentadbiran di daerah masing-masing.” (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 280).

1889-07-22: Tengku Mahmud menjadi Pemangku Raja

“Pada 22 hari bulan Julai 1889 itu juga Sultan Ahmad telah mengangkat dan melantik putera sulung baginda Tengku Mahmud menjadi Pemangku Raja bagi negeri Pahang, kerana usia baginda telah bertambah lanjut dan telah merasa uzur hendak menjalankan tugas yang berhubung dengan pentadbiran pemerintahan. Baginda telah menyerahkan segala urusan pemerintahan negeri Pahang kepada Tengku Mahmud dan beliaulah juga yang akan menjalankan rundingan dengan Residen British Pahang bagi mengadakan undang-undang dan menjalankan peraturan dalam negeri, dan baginda telah menyatakan juga kepada semua orang besar dan ketua dalam negeri Pahang supaya mentaati perintah anakanda baginda itu seperti kepada baginda juga.” (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 283-284).

1889-12: Sultan Ahmad Berpindah ke Pulau Tawar

“Di dalam bulan Disember 1889, Sultan Ahmad yang bersemayam di Pekan telah berangkat pindah bersemayam di istana baginda di Pulau Tawar, dalam daerah tempat kediaman Tok Gajah, tempat itu jauhnya hampir seratus dua puluh batu ke hulu dari Kuala Pahang. Pada tahun hadapannya, tahun 1890, baginda tidak pernah berangkat datang ke Pekan. Jika ada urusan negeri yang hendak dirundingkan dengan baginda, terpaksalah dibawa ke Pulau Tawar.” (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 287).

1889-1893: Peringkat Awal Perlombongan di bawah British

Pada peringkat awal kegiatan perlombongan ini, pelbagai kesukaran dialami, namun setelah kemudahan perkhidmatan pengangkutan dan hospital dibangunkan oleh pihak syarikat, dari kawasan perlombongan di Sungai Lembing sehingga ke muara Sungai Kuantan, keadaan menjadi beransur baik: “The difficulties of those early years, which were successfully overcome, were mostly of a physical character. The almost complete isolation of Sungei Lembing was the first challenge to be met. Although the area had been surface worked in a primitive manner for more than 100 years by the Malays and Chinese, without the use of explosives and only by an open cast system of mining, the territory was still virtually jungle-locked without roads or railways, and was quite inaccessible except by river from the port of Kuantan, 40 miles away. Kuantan, 200 miles by sea from Singapore, was itself isolated. There were no ships regularly sailing to Kuantan. In uncharted waters, navigation and entry into the mouths of the rivers on the east coast of Malaya, were always hazardous, and during the north-east monsoon season often four months would elapse without supplies inwards being landed at Kuantan from Singapore, or the Corporation's output of tin being shipped away to Singapore. At one time the then agents of the Corporation in Singapore, Messrs. Paterson, Simons & Co., had to charter a vessel, the Pilot Fish, to serve Kuantan, whilst a little later Mr. Neild had to purchase a steamer, the S.S. Perse, in an endeavour to ensure that a ship would call at Kuantan regularly twice a month; once, recourse was made to the use of native sailing craft. Wharves, warehouses and associated facilities, including a hospital, had to be built and provided almost immediately at Kuantan by the Corporation, and it is true to say that Kuantan owed its existence to the Corporation's activities and enterprise in Pahang in those early years. … There were no government hospitals in Sungei Lembing and Kuantan in 1890, and it was therefore expedient for the Corporation, at its own expense, to build a hospital in each of the two towns, both of which were then maintained and run by the Corporation and its medical officers. These institutions dealt not only with the European staff and labour force of the Corporation over the years, but they also succoured and cared for all and sundry, including Government Police, P.W.D. personnel, and others who needed medical attention in the Kuantan and Sungei Lembing districts.” (Pahang Consolidated Company, 1966: |"Sixty Years of Tin Mining: A History of The Pahang Consolidated Company - 1906-1966: I. The Pioneering Years - The Pahang Corporation" (PDF), m.s. 16, 18).

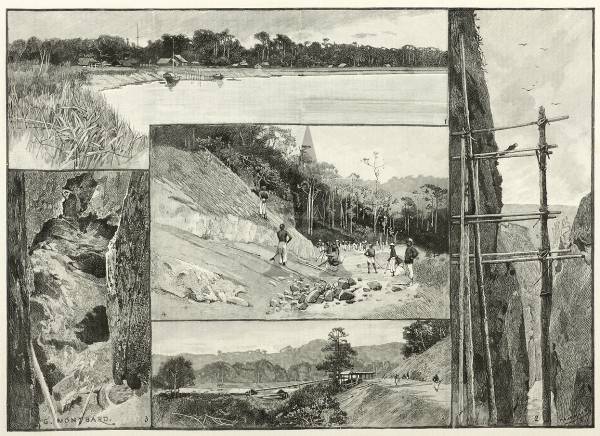

Operasi perlombongan di Pahang (1890): 1 (Atas): “Kuala Rumpen (Rompin) Pahang” 2 (Kanan): “Nicholson’s Tin Lode, Pahang Corporation.” 3 (Kiri): ”Smyth’s Tin Lode, Pahang-Kabang Limited.“ 4 (Tengah): “Chinese constructing Tramway and Water-race, Pahang Corporation.” 5 (Bawah): “Tin Stamping Mill, Pahang Corporation.” (G.Montbard, 1890: |"Mining Operations at Pahang, in the Malay Peninsula").

Pelabuhan utama syarikat ini terletak di kuala Sungai Kuantan, ketika itu Kampung Kuantan. Di sini, setiap hasil bijih timah yang dibawa dari hulu sungai sejauh 40 kilometer, akan diturunkan di sini, dan seterusnya dipersiapkan untuk dibawa ke Singapura:-

“Kuantan is the most northerly of the Pahang river districts, and it has one of the nastiest bars, upon which the waves break with extraordinary fury except in the calmest weather. It is distant from Singapore about 240 miles, say a day's journey. Bold hills guard the northern bank of the river, and somewhat mitigate the severity of the monsoon weather within the Kuala. Once inside, a deep winding river, navigable for ships of light draught for many miles, forms an excellent harbour. On the left bank stands the Pahang Corporation wharf, a large godown, and several houses and bangsals also belonging to the Company. The official village of Kuala Kuantan consists of a police-station, court-house and the Magistrate's bungalow. The commerce of the place is housed in a row of attap erections. The Government has also a wharf, a busy place, the resort of native boats to the number of perhaps half a dozen per month. But then natives have prejudices with regard to policemen and government officials, from their invariable assocation with taxation. The elaborate system of passes, licenses, and fees in Pahang seems to make that prejudice not unfounded.

Kuala Kuantan is the port of the P.C., Ltd. There all stores are received, housed, and despatched upstream in flat bottomed boats. All tin-ore down stream is here landed, checked, and shipped. The Agent of the Corporation, and the Magistrate, hold about equal sway, the balance of power lying possibly with the former, since with him is the hope of the rich reward that sweetens the not too exhausting labours of the Malays of the river. Without the Corporation's Agent and the money he disburses for wood-cutting, cargo working, and boat hire up and down the river, Kuala Kuantan would be a mere fishing village, for although Tringganu men come and build marvellously solid boats of a hard wood called chinghal, the men of Kuantan are content to go to sea in fine weather and catch a few fish. Fish and large families foregather in Kuantan.”

(Sumber: The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 27 October 1897 & Weekly @ 2 November 1897: |"THE PAHANG CORPORATION, Ltd.").

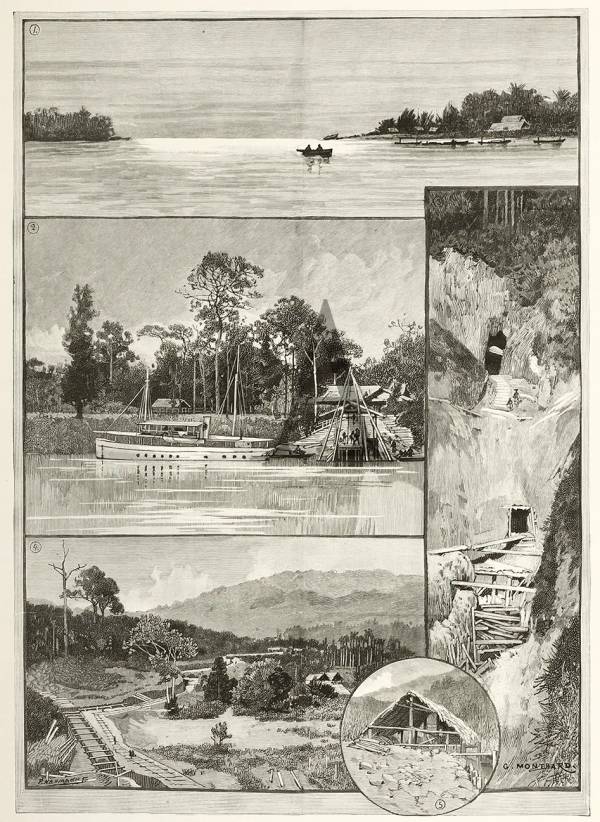

Kampung Kuantan @ Kuala Sungai Kuantan (1890): “C19th engraving of Malaysian tin mines. Inset titles:

1. Entrance to the Kuantan River, where the Pahang Corporation are working.

2. Batu Sawah, the landing-stage sixteen miles up the Kuantan.

3. Campbell's Tin Lode (Pahang Corporation). Showing ancient workings.

4. Sungei Lambing District, where the Pahang Corporation are working their mines.

5. Native Chinese Tin-Stamping Mill, on the Kuantan.

From the original edition of the Illustrated London News.” (G. Monetbard, 1890: |"Mining Operations in the Malay Peninsula").

Pada tahun 1893, denai sepanjang 12 batu telah diterokai merentasi hutan dari Sungai Lembing ke Kuala Reman (kira-kira separuh jalan ke Kuantan). Setelah itu, masa perjalanan di antara Sungai Lembing ke Kuantan dapat dipendekkan (asalnya 2-15 hari, mengikut keadaan paras air sungai): “By 1893, a track through the jungle was cut from Sungei Lembing to Kuala Reman, a point about 12 miles down stream. A specially designed shallow draught stern-wheeler sent out from England was then able to get up the river as far as Kuala Reman, and the journey from Kuantan to Sungei Lembing, which on one occasion took 15 days and rarely less than two, was appreciably shortened. Even so, for years after, the journey by river was unreliable, since it was so often either in flood during the monsoon season or, in the dry season, there was insufficient water in its upper reaches, and in quite recent times the river was not navigable above Pasir Kemudi.” (Pahang Consolidated Company, 1966: |"Sixty Years of Tin Mining: A History of The Pahang Consolidated Company - 1906-1966: I. The Pioneering Years - The Pahang Corporation" (PDF), m.s. 16).

Pemberontakan Dato' Bahaman, bersama Tok Gajah dan Mat Kilau mulai akhir tahun 1891 menambahkan lagi cabaran kepada pengusaha lombong. Pada akhir tahun 1893 hasil perlombongan di Pahang didapati masih belum memuaskan. Kesannya, Residen British membatalkan banyak konsesi perlombongan di Pahang, dan tiada pelaburan baru di sektor ini untuk tahun 1894. Pada tahun 1895, hanya lombong-lombong lod sedia ada sahaja (termasuk Pahang Corporation) yang masih aktif:-

“Many of the concessions, obtained as speculations, were never prospected. Others were prospected in a desultory manner by European companies which turned their attention elsewhere without starting serious mining operations. At the end of 1893 some twenty of these unworked concessions were cancelled. Most of the other concessions were under some form of European ownership or control. Concessions with alluvial tin deposits were the first to be brought into production (fig. 19). Since the equipment needed was not elaborate, and the scale of mining could be varied to suit the labour force available, companies at Bentong, Sungei Dua, and Belat, the latter near present day Gambang, began work as soon as their indentured Chinese labourers arrived from Singapore. Tin was being exported within twelve months but the obstacles quickly became apparent. Living as they were in freshly made clearings, management and labourers alike suffered from malaria and the mortality rates were very high. Direct supervision of inexperienced Chinese labourers by European managers, who also lacked experience, was not a success and differences which arose were aggravated by ill health and isolation. In 1890 serious work ceased at Sungei Dua and Belat and the companies involved transferred the remnants of their labour forces to lode mining properties. The Bentong Company exported “a considerable amount” of tin ore in 1890 but was unable to recommence work after a stoppage caused by the rebellion of the local chief at the end of 1891. … It was clear that Chinese mining, with its more flexible organisation and lower overhead costs, would be better able to exploit these alluvial deposits.” (Dr. R.G. Cant, 1973: |"An Historical Geography of Pahang" (PDF), m.s.44).

“Lode mines could not be developed rapidly. More substantial buildings were required and the task of importing crushing and pumping equipment was a difficult one in a land where rivers and jungle paths were the only lines of communication. In each case heavy equipment was taken inland by river and then dragged overland from river landing places to the mines (fig. 1 g). Some of the machinery intended for mines at Selinsing was taken up the Pahang and Jelai Rivers to Kuala Medang but never reached the site of the workings. Another company at Ulu Kuantan attempted to avoid such problems by locating its plant at Baias on the Kuantan River. By the end of 1891 this company had erected elaborate crushing equipment, complete with an eight head stamp, dressing floor and wells, in addition to building a tramway, numerous bungalows for European staff, and a substantial hospital. All that was lacking, commented the writer of the Pahang Annual Report for that year, was a lode of tin in the vicinity of the mill which would repay the cost of working.” (Dr. R.G. Cant, 1973: |"An Historical Geography of Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 46).

“By the end of 1893 the records make it clear that there were only four European mining companies engaged in serious work in Pahang. There were the three companies mining gold at Raub, Penjom and Selinsing, and the Pahang Corporation working the tin lodes at Sungei Lembing. Although some minerals were being produced (figs. 20 and 21), output bore no relation to capital expended and it was as yet too early to assess the eventual profitability of such mines. It was very clear, however, that European mining in Pahang had not been established on the scale envisaged by the optimists of the 1880's. European attempts to mine alluvial tin had failed and the more successful ventures of men like L.J. Fraser were the result of entrepreneurial rather than mining skill. With only four companies in operation, and approximately one thousand labourers employed, European mining had been established on only a modest scale and it remained to be seen whether these ventures could survive on a permanent basis. In view of the considerable capital expenditure and the high ratio of European staff it was clear that a considerable output of minerals, and a marked reduction in overhead costs, would be required if the companies were to continue in operation. At the end of 1893 the British Resident cancelled some twenty of the concessions and noted in his report that “Government now has at its disposal large areas of mining and agricultural land”. There was, however, no influx of new capital or population into Pahang in 1894. The first flush of optimism was over and neither Europeans nor Chinese were attracted by the new image which was emerging. Europeans were unwilling to introduce new capital until the existing ventures had proved themselves to be economically sound and the Chinese were too busily engaged in the western States where communications were well developed, overhead expenses considerably lower, and returns more assured. In 1895 it was officially recognised that apart from the activities of the lode mines, mining development in Pahang was at a standstill. The mining policy initiated by Rodger in 1889, and carried on by his successors, was administratively sound but its long term consequences were unfortunate. The effective opening up of Pahang was delayed at a critical time when the western States had already entered a phase of sustained and cumulative economic development. In Selangor, Perak, and Negri Sembilan, economic opportunities were expanding faster than the tin reserves were diminishing and Pahang lost much of its attractiveness in consequence. During these first four years the new economic penetration of road less Pahang was made with comparatively slender private resources. Small European mining ventures were unable to make that initial conquest of the forest environment necessary to overcome a high level of endemic disease. Chinese syndicates which could more readily have come to terms with the environment were largely excluded. Larger European enterprises were too few, and communications too meagre, to produce external economies which might reduce their overhead costs. Their total investment was not inconsiderable but in the absence of parallel investment in the public sector any immediately cumulative effects were lost in the vastness of this sparsely settled State.” (Dr. R.G. Cant, 1973: |"An Historical Geography of Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 45-47).

1888-1891: Peningkatan Populasi Warga Tionghua

Seiring dengan perkembangan perlombongan ini, populasi warga Tionghua di Pahang kembali meningkat:-

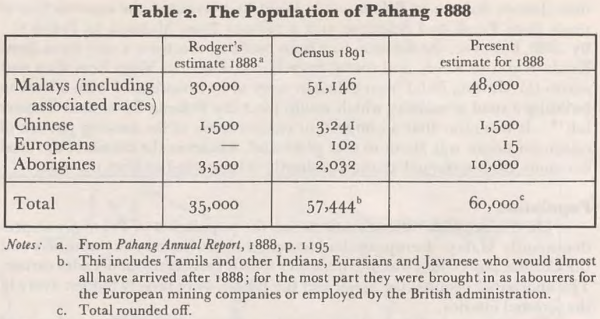

“Table 2. The Population of Pahang 1888”

“The majority of the 3,241 Chinese enumerated in the 1891 census would have entered Pahang after the beginning of British rule and the introduction of regular steamship services from Singapore to Kuala Pahang and Kuantan. The total in 1888 was certainly not greater than Rodger's estimate of 1,500. Most of the Chinese were found in the town of Pekan where there was a Chinese quarter, the trading village of Penjom, and in the mining areas in Ulu Pahang and Ulu Kuantan. During the drier period of the year, from March to November, small groups of Chinese engaged in timber extraction could be found in areas which were easily accessible from the coast and not permanently inhabited by Malays. The Pahang River was regularly used by Chinese traders, and Swettenham in 1885 had noticed a number of small Chinese sugar mills on the left bank of the Pahang River between Pulau Tawar and Temerloh. Chinese traders had been living among the Malays in the Tembeling Valley when Mikluho-Maclay passed through there in 1875 but there is good reason to believe that the existence of individual Chinese among the Malays in such remote areas could have only been temporary in the decade that followed. By 1888 the Chinese population which survived in Pahang had concentrated itself into a few mining areas and trading centres in an effort to achieve greater security.”

(Sumber: Dr. R.G. Cant, 1973: |"An Historical Geography of Pahang" (PDF), m.s.31).

1890-an: Kegiatan Perikanan

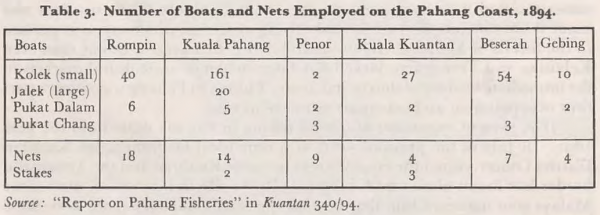

“Fishing in Pahang was either a part time occupation or an inadequate source of income. The present expansion of coastal fishing in Pahang dates from the year 1891. In July of the previous year, at a time ideal for fishing, the Kuantan District Officer visited the coastal areas between Kuantan and the Trengganu border but found almost no fishing activity. He did, however, meet some Malays who informed him that beyond the State boundary there were those who would come and settle “for a little money”. The District Officer was unable to oblige in this respect but he must have generated some confidence for they came nevertheless. At the end of 1891 he reported that “the fishing

industry, carried on principally by Trengganu Malays who have settled along the coast, is increasing rapidly and I hope that by encouraging settlers at the mouths of some of the small coast rivers, all of which are scantily populated, permanent villages and plantations may gradually spring up”.

In 1894 the Kuantan District Officer compiled a detailed report on the fishing industry in Pahang. This report is significant not only for the descriptive and statistical material which it contained, but also for the policy which

it formulated at that date.

According to the report there were well over 300 boats of various kinds operating from the Pahang Coast in 1894 (Table 3). Some 48 of these were boats exceeding 30 feet in length, and 20 of the boats based at Kuala Pahang

were jalaks which could venture out to sea in moderately rough weather. The majority of the fishermen employed were of “the lowest class of Kelantan and Trengganu Malays” who either “return to their homes at the end of the season”

or, being without employment during the north-east monsoon, “relapse into petty theft or more serious offenses relating to property”. The writer further commented that the reason always given by newcomers arriving from Trengganu or Kelantan was that “their former headman has recently removed from that district”. There is also evidence that a number of Chinese fish merchants from Trengganu moved to settle in Pahang at this stage and their activities are reflected in a steady increase in exports of dried fish. Immigrant Malay labour, Chinese entrepreneurship and the security of British rule thus appear to be the three main factors in this re-establishment of the Pahang fishing industry. Much remained to be done, however, before the economy of the coastal fishing settlements was placed on a satisfactory footing. The author of the report realised the advantages of permanent settlement and the need for supplementary sources of income. He thus recommended that the fishermen be given free grants of land for planting and rice cultivation.”

“Number of Boats and Nets Employed on the Pahang Coast, 1894”.

“The administration adopted this policy but for various reasons the results were not satisfactory. In the first place rice cultivation was held in no higher regard by the fishing population than by the local Malays in the coastal districts. Even more serious was the fact that the months for the preparation and planting of coastal padi coincided with the best fishing months. In addition, the administration retained all the land which might be required for commercial purposes and limited their special grants to the sandy and infertile land immediately adjacent to the coast. A number of plots were taken up in 1895, chiefly between Beserah and Batu Hitam, but over 30 percent of the trees planted were blown over or washed out the following year. Matters were not improved when the administration decided to charge quit rents on land alienated to fishermen settlers and in 1898 a number of settlers left Pahang and moved into Trengganu because they were required to pay quit rent for one of the few areas which had been taken up for coastal padi. In spite of these and similar frustrations, the fishing population continued to increase during the next decade and more settlements were established at various points along the coast. Some planted coconut trees but none were willing to persevere regularly with wet padi. To this day the fishing settlements of Pahang have an inadequate agricultural base and the standard ofliving there is the lowest in Malaya.”

(Sumber: Dr. R.G. Cant, 1973: |"An Historical Geography of Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 59-60).

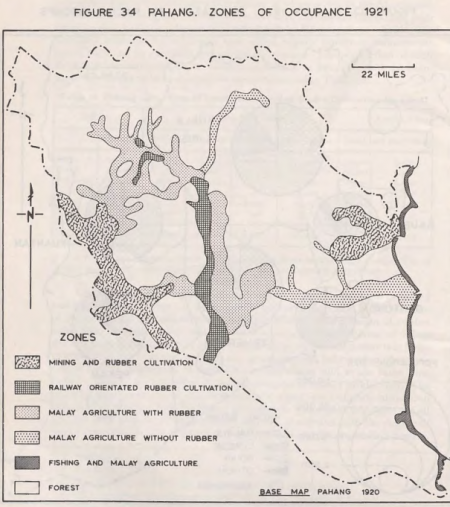

1890-an: Kegiatan Pertanian

“In the first four years of British administration a few of the concession holders made desultory attempts to explore the agricultural potential of their lands. The Pahang Corporation, who initially held rights over the watersheds of the Kuantan, Rompin and Endau Rivers, did this more seriously than most. Their agent, A.J.G. Swinney, spent most of 1889 and 1890 exploring the Rompin River and reported favourably on its possibilities. No minerals were found, however, and the Corporation decided to confine its activities to the Kuantan District. There they made experimental plantings of tobacco, pepper, and coffee, and imported plants of nutmeg and pepper which they distributed to Malays who were encouraged to grow them on special grants of Corporation land. In most cases the plants grew well but both the Corporation and the Malays were too preoccupied with other activities to persist

with cultivation.

…

In 1898 a party of Malacca Chinese arrived at Kuantan in search of new land for tapioca and the following year they were permitted to open up two estates on hilly land which the District Officer described as too sandy and useless for any other purpose. About the same time some of the European and Chinese entrepreneurs already resident in Pahang took up land in the vicinity of Kuala Kuantan and Kuala Pahang. By the turn of the century they had established four coconut estates, each of several hundred acres. Commercial agriculture was established but on a very modest scales.”

(Sumber: Dr. R.G. Cant, 1973: |"An Historical Geography of Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 62-63).

1891-1894: Pemberontakan Datuk Bahaman bersama Tok Gajah dan Mat Kilau

Ramai pihak tidak senang dengan perlantikan wakil (kemudiannya Residen) British di Pahang, terutamanya Datuk Bahaman (Orang Kaya Semantan). Keadaan ini mencapai kemuncaknya apabila Tengku Mahmud (pemangku Sultan Ahmad) menghadkan bayaran gaji kepada pembesar-pembesarnya, di atas nasihat pemangku Residen, Hugh Clifford. Berikutan itu, Beberapa pemberontakan menentang British di serata negeri Pahang, diketuai oleh Dato' Bahaman dan para pengikutnya: Tok Gajah, Mat Kilau, dan Mat Kelubi. (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 297-351).

Sumber lain: “Mining in Pahang had languished since the 1850s but the reputation of the state as one of unbounded riches remained. Here the sultan continued to exercise effective authority and decided to take advantage of the gold fever of the early 1880s to grant extensive concessions. One of these covered tin deposits which had already been proved by Chinese and Malay miners and in 1886 it was acquired by London interests who floated it as Pahang Mining Company. A Cornish mining expert provided a very favourable and honest report which would see the property developed as a large lode mine. This would require a more secure title, one that only a British administration could provide and in 1888 the sultan agreed to accept a British Resident. That prompted a rebellion on the part of some Malay chiefs which required British support to subdue.” (John Hillman, 2010: |"The International Tin Cartel" (PDF), m.s.34).

Pencetus pemberontakan bersenjata: tindakan C.E.M. Desborough: “Pada 15 hari bulan Disember 1891 itu, C.E.M. Desborough yang menjadi Pemangku Pemungut Cukai Tanah di Mukim Semantan serta seorang inspektor lombong yang membawa lima belas orang mata-mata bangsa Sikh dan enam orang matamata Melayu, telah mudik di Sungai Semantan pergi ke Lubuk Terua untuk menambahkan bilangan mata-mata di balai polis di situ. Semasa dalam perjalanan Desborough telah berjumpa dan menangkap tiga orang pengikut Datuk Bahaman yang telah dituduh mengeluarkan hasil hutan dengan tidak mempunyai surat kebenaran daripada kerajaan. Desborough tidak mahu melepaskan mereka walaupun kaum keluarga mereka mahu menjamin, mereka telah dibawa ke balai polis Lubuk Terua ditahan untuk dibicarakan. Oleh sebab Datuk Bahaman memikirkan pasukan British yang datang itu telah dirancang untuk menangkapnya, beliau telah bersedia menghimpunkan pengikutnya. Pada hari yang kedua, pasukan Desborough telah diserang hendap oleh orang-orang Datuk Bahaman dan berlakulah pertempuran. Beberapa buah perahu pihak British telah ditenggelamkan oleh orang-orang Datuk Bahaman, inspektor lombong itu serta seorang Melayu pengayuh perahu dan seorang mata mata Sikh telah luka. Oleh sebab tidak dapat menentang serangan itu, Desborough dan mata-mata Sikh yang dibawanya itu telah lari semula ke Temerloh dengan menggunakan beberapa buah perahu yang ada pada mereka. … Setelah berjaya menyerang dan mengalahkan pasukan Desborough itu, Datuk Bahaman dan pengikutnya telah pergi menyerang dan menawan balai polis di Lubuk Terua. Kemudian mereka menyerang dan berjaya menawan rumah stor kepunyaan syarikat lombong di Raub dan di Bentong dan mengambil makanan dan barang yang tersimpan di situ. Pada masa itu Datuk Bahaman telah terus terang menyatakan maksudnya hendak menentang pihak British yang menjalankan pemerintahan di negeri Pahang dengan menggunakan senjata. Kejayaan Datuk Bahaman mengalahkan pasukan Desborough di Sungai Semantan itu telah membangkitkan semangat berani orang-orang Melayu di Semantan menentang British, dan telah mengambil ramai lagi orang Semantan menjadi pengikutnya. … Tiada lama kemudian, angkatan Datuk Bahaman telah menyerang pekan Temerloh. Desborough dan mata-mata yang mengawal tempat itu telah lari meninggalkan pekan Temerloh. … Pada masa itu Datuk Bahaman dan pengikutnya telah berjaya menguasai daerah di Sungai Semantan hingga ke Temerloh.” (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF),m.s. 302-304).

Pemberontakan berakhir dengan kekalahan pihak Datuk Bahaman di Jeram Ampai pada 29 Jun 1894: “Pada pagi 29 hari bulan Jun 1894, pasukan besar pihak British dari Kuala Tembeling telah bergerak hendak menyerang pasukan Tok Gajah, Tok Bahaman dan Mat Kilau di Jeram Ampai. … Tiada lama bertempur, pihak Tok Gajah dan sekutunya itu dapat menahan tembakan dari pihak British itu, lalu Tok Gajah, Tok Bahaman, Mat Kilau dan pengikut mereka berundur meninggalkan kubu mereka di Jeram Ampai mudik ke hulu Sungai Tembeling ke Hulu Lebir (Kuala Ampul) di Hulu Kelantan. … Dari pihak orang Melayu yang menentang pihak British itu pula mengatakan kekalahan di Jeram Ampai ialah kerana orang-orang Pahang telah belot kepada mereka dan telah menolong orang putih. … Walaupun serangan pihak British di Jeram Ampai itu telah dilancarkan dengan pimpinan yang kurang baik, tetapi sejak itu boleh dikatakan tamatlah pertempuran di negeri Pahang yang dibangkitkan oleh orang Melayu yang menentang pihak British yang telah mencampuri pemerintahan di negeri Pahang itu, kerana pemimpin mereka itu telah berundur ke negeri Kelantan dan Terengganu.” (Haji Buyong bin Adil, 1972: |"Sejarah Pahang" (PDF),m.s. 350-351).

1895-06-12: Perjanjian Persekutuan

Di dalam Perjanjian Persekutuan pada 12 Jun 1895, Negeri Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan dan Pahang disatukan menjadi Negeri-Negeri Melayu Bersekutu. Antara punca Pahang turut serta di dalam persekutuan ini ialah masalah kewangan berikutan pemberontakan sebelumnya, serta kekangan-kekangan di dalam kegiatan perlombongannya, yang dapat diselesaikan dengan penggabungan ini. (Pahang Consolidated Company, 1966: |"Sixty Years of Tin Mining: A History of The Pahang Consolidated Company - 1906-1966: I. The Pioneering Years - The Pahang Corporation" (PDF), m.s. 12).

“It is against the background of growing European mining interests that the final moves towards consolidating British rule over the whole peninsula were made. A confederacy of several autonomous states, including Sungei Ujong, was constructed as Negri Sembilan and made part of the Residency system. Repression of the Pahang rebellion had left that state bankrupt and in 1895 its sultan, together those of Negri Sembilan, Selangor and Perak,signed a Treaty of Federation and the Federated Malay States (FMS) was brought into being.” (John Hillman, 2010: |"The International Tin Cartel" (PDF), m.s.35-36).

Setelah Pahang berada di bawah naungan British, Sultan Pahang membatalkan sebahagian daripada konsesi yang telah dianugerahkan kepada Pahang Corporation pada tahun 1888, iaitu terhad kepada bahagian daerah Kuantan selepas Kuala Reman. “The initial selection of Mr. Neild and his appointment in 1890 had been influenced by the British Resident in Pahang who, in his Annual Report for 1889, had expressed the view that: ” … it is more important that an Eastern Mining Manager, who must necesarily be entrusted with very wide powers by the Director of his Company, should be a capable man of business, accustomed to life in the East, than that he should possess the practical mining experience which can be readily supplied by his subordinates …. ” There is no doubt that it was these views, and the success of Mr. Neild, which influenced the Directors of the Corporation to choose as his successor a clerk who had already been some years in their employ. He was Mr. W. H. Derrick and he succeeded Mr. Neild as Superintendent in 1895 and held this responsible position for ten years to 1905. Less than a year after the appointment of Mr. Derrick, difficulties again arose over the Corporation's Concession. It was the year after the State of Pahang became one of the protected Malay States to be administered under the advice of the British Government. Suddenly the Sultan of Pahang, acting under the control of the State's Government, cancelled from the Corporation's 1888 Concession, the outlying portion of the territory belonging to the Corporation, and its rights were restricted to that part of the Kuantan district above Kuala Reman.“ (Pahang Consolidated Company, 1966: |"Sixty Years of Tin Mining: A History of The Pahang Consolidated Company - 1906-1966: I. The Pioneering Years - The Pahang Corporation" (PDF), m.s. 14).

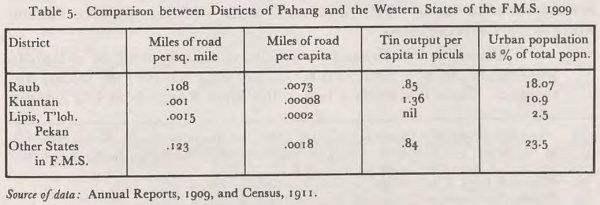

Pada tahun yang sama, pembangunan jaringan perhubungan dan pengangkutan di antara Perak, Selangor, dan Pahang bermula dengan pesatnya, antaranya jalan Kuala Kubu - Kuala Lipis (1895-1896), yang menggalakkan penghijrahan tenaga pekerja dari pantai barat ke sepanjang jalan tersebut, termasuk pembukaan beberapa lombong kecil di Raub dan Tras. Pada tahun 1897, pengusaha lombong terkenal di Selangor, Loke Yew, dianugerahi sebuah konsesi seluas 4,000 ekar di Bentong. Perlombongan besar-besaran di situ beroperasi setahun selepasnya, bersama dengan pertumbuhan bandar-bandar baru serta jaringan jalan raya, termasuk Bentong-Tranum-Tras. (Dr. R.G. Cant, 1973: |"An Historical Geography of Pahang" (PDF), m.s. 48-49).

1897-1900: Kegemilangan Pahang Corporation